The weather trapped us in a six day snowstorm, but we still managed to climb on this wonderful remote Island. The mountains seem to go forever, and with so many still unclimbed, this is a climbers paradise!

Named after the British explorer William Baffin – Baffin Island is one of the largest islands in the world.

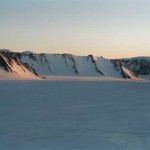

Much of its landmass sits inside the Arctic Circle, and is a continuous run of glaciers, mountains and fjords. In places the sea ice only breaks for a few weeks a year, and the land is covered in permafrost. In summer there is almost endless daylight, yet in winter the sun barely rises above the horizon.

“Why would anyone want to go to such an inhospitable sounding place” you may ask. Because of the solitude, the endless mountains, the pristine country and the emptiness.

Baffin sits in the province of Nunavut, which has a landmass equivalent to Western Europe, but contains only 27,000 people. It is a true wilderness.

Situated on the edge of the Cumberland Peninsular, Pangnirtung is a small community of mainly Inuit people. The town lines the fjords edge with its brightly coloured houses, shops and government buildings. There is little room for luxury here, but a close community spirit is obvious, and sustains the town year in, year out.

The old Hudson’s Bay Company Whaling Station building still stands battered by the many winters, which have ravaged its woodwork, marking the reason why such communities grew. Whaling and trading were big business when this country first opened up to western traders.

For ten months of the year the fjord is completely frozen over so the main form of transport is the skidoo, though a few roads in town allow vehicles and cycles to be used.

Pangirtung became our base from which to break out onto the main ice-caps and glaciers.

Auyuittuq National Park Reserve, or “the land that never melts,” was established in 1975 as the first national park north of the Arctic Circle. It covers 21,500 square kilometers of the Cumberland Sound Peninsula and is made up of mountain valleys, fjords, and glaciers.

Many visitors to the park come to walk through the Akshayuk Pass between the communities of Pangnirtung and Broughton Island, but we were climbing in a much more barren and unexplored area west of the pass towards the Penny Ice Cap. Few people venture here because of the remoteness of the area, preferring to walk past such monstrous mountains as Thor and Asgard, with their 3000ft vertical granite walls.

We came to climb Tete Blanche, the highest mountain on the island, and to explore and climb around the Penny Ice Cap. It was a daunting task to undertake.

Inuit peoples have lived in Arctic conditions for centuries, surviving the sub zero temperatures winter darkness, to be rewarded with short, but warm and bright summers.

Their culture has developed a strong community spirit embracing traditional arts and sports, throat singing and even Scottish Dancing!

Though western influences have changes their lifestyles, they still hunt and fish out on the ice, and survive in some of the most inhospitable conditions on the planet.

Today many live in modern towns working within their communities, but also offer outfitting services to take people out onto the glaciers for expeditions and tourism.

A team from Pangnirtung transported the expedition onto the Penny Ice Cap using Skidoos and Sledges, and brought us home after our time on the ice. They are a wonderfully easy people to get on with, and their hospitality is second to none.

Nanuk, or the ‘Great White Bear’ has lived on the ice for thousands of years. Hunting predominantly along the shores edge for seal pups, the Polar Bear is the ultimate predator for the Arctic. An adult male can weigh in at almost 1000lb, can be 10 ft long from nose to tail and can run and swim much faster than any human. For the arctic traveller they are a considerable danger.

Simple precautions can prevent any confrontation. Don’t leave food around, always keep a sharp lookout, and keeping downwind are but a few.

The risk of bears was small on the ice-caps due to the lack of natural food, but we kept a lookout at all times just in case.

Fortunately we never sighted a bear, but the danger is real and deadly.

Traveling to remote places such as Baffin Island is not a cheap pastime. Flights and the amount of specialist equipment needed for such an undertaking is expensive and hard to organise. High-energy food is needed, and back up contingencies required, all bringing with them extra costs.

Though I received no monetary assistance for the expedition I did receive equipment from both Terra Nova and Sealskinz.

Terra Nova have helped me on many of my recent expeditions and provided me with a Super Quasar tent, which survived all that the weather could throw at it.

Sealskinz provided me with waterproof breathable socks to protect my feet against the reoccurring dangers from frostbite. They worked excellently keeping my feet dry in the arctic cold.

Towing a pulk, or sledge laden with all your equipment and supplies for three weeks is no easy task. The condition of the ice and snow can make pulling anything from hard to impossible, rocks carve gouges out of the sledge bottom, they regularly turn over, and either push or pull you in every direction except the one you wish to go. Fully laden our pulks weighted in at around 150lb each.

They are however the best way of transporting your equipment with you. They distribute out their weight well, so as not to fall through crevasses, they provide excellent storage, float, and can be used in many emergency situations.

Imagine how much food and equipment you would need for three weeks at home. It would be impossible to carry such a weight, so we work with lightweight gear and dried food, and pack everything into each pulk. The best thing is that the more you travel, the more you eat, and lighter your load becomes!

Modern western society brings with it many conveniences. Electric light at the touch of a button, food that is simple and quick, fast modes of transport and cross-world communications. We also maintain a high state of cleanliness. As soon as you walk onto an ice cap many of these conveniences disappear.

Your only light is a torch, which has only as much power as you have batteries.

Food can be difficult to cook, and need fuel, which you have to carry with you.

Transport is reduced to mainly your own two feet and how far you can carry yourself and your equipment.

Satellite telephones have made communications easier, but even they do not work all the time.

You can only wash and change clothing when you return to base, so for seventeen days we survived in a state of sticky sweat and dirt.

Sitting stuck inside your tiny tent on a glacier is hardly the dream of any arctic adventurer. The weather can be brutal, and from personal experience I know that however boring, irritating and depressing the weather can be the safest thing to do is sit it out.

After five days on the glacier dark clouds closed in, the wind increased, and it was impossible to move safely. We were stuck for the next six days, windswept, snow drifted and bored in our cocoons of nylon and Gore-Tex.

Anyone can stand a day, even two, but I soon noticed that the delays were irritating people. All we could do was wait for the weather to clear, but with a finite time span to work with, everyday in the tents made climbing Tete Blanche a more distant possibility.

After being stormbound in the tents it was wonderful to see the clouds break and the sun come out. It was only mid morning though, and it seemed such a waste of a day if we didn’t do something.

Across from camp was the highest ice cap on Baffin. Though not a major expedition objective it did provide an excellent way to lift morale and at least get some climbing in.

The approach was on skis, and after a six-hour slog we stood on the 7200ft summit. Around us lay mile after mile of unspoiled mountain wilderness. Tete Blanche stood to our north, but it was now apparent that we could not attempt to summit because of the time constraints now put upon us. We were higher than Tete Blanche, so I can claim to have stood on the highest piece of Baffin.

By the time we had returned to base camp the sun had set, it was -20C and we were all shattered. Warmth and sleep could not come quickly enough.

It is easy to be overrun with emotion when in the mountains, and to allow that emotion to cloud decisions, which can be vital to survive. Many people have suffered from ‘summit fever’ and paid the price with their lives.

We attempted to climb a new route near our camp. It was a mixed route on ice, snow and rock, and we wanted to be the first people ever to step off the route onto the mountains summit. The conditions were near perfect when we started, but after only a few hours on the mountain the weather clouded in, the wind grew in strength and the conditions became dangerous. We took the decision early to retreat for the safety of camp.

If we had stayed on the mountain we could have been stuck in a blizzard fighting for our lives. As it was we were safe and warm in our tents.

When I returned home everyone’s first question to me was ‘how did it go?’ The second was ‘what’s next?’ As of yet I do not know. I have many ideas, but as of yet none of them have materialised.

My experiences on Baffin have changed me forever, as now I know that I can survive on a glacier again and come back unscathed.

Perhaps the challenges have changed as I have, and I need something new to drive me, but as ever adventure is always in my heart.

I will wait to see what the future brings over the coming months, as now I do not need to find new challenges and adventures – they see to find me!

Great write-up. I dream of visiting this region and exploring.

Its a very beautiful part of the world Benjamin…