Working the indigenous Amerindian people of Guyana was an incredible experience. They still live a traditional life and we in the western world could learn so much from them. Guyana holds many of natures wonders including the 741ft high Kaiteur falls and some of the last unspoiled Amazonian Rainforest….

Guyana offers almost endless opportunities for expeditions into untouched and often unexplored areas. Many of the indigenous Amerindian peoples still live a traditional life; we can learn so much about ourselves from how they live. The word Guyana is Amerindian for “Land of Many Waters” I find the jungle a wonderful place in which to live. Nature surrounds you, covering the landscape in a dense green carpet of unspoilt forest full of rare plants and animals. I find living with nature a relaxing and rewarding experience. The tropics provide an extremely difficult climate in which to work, requiring a high degree of both mental and physical fitness. Finally there is the chance of seeing something unexpected in such an unexplored country.

Over two years of planning and training were needed before the expedition was ready to leave for Guyana. The planning was carried out by a group of like-minded people all volunteering their time and skills. The expedition was split into four groups: – Medical, Construction, Environmental and Adventure. There were over forty people making up the groups from all walks of life: – Firemen, Joiners, Engineers and Nurses to name but a few. All had to be taught expedition skills such as firelighting, water purification, hammock slinging and first aid. I was a member of the adventure group and was able to learn new skills, and because of previous jungle experience, teach others. Our project was to re-build a water supply in the village of Karasabai, then undertake a six day trek to Kato before meeting all the other groups at Kaiteur falls.

We arrived in Guyana late on 27th September 1997. A night time truck ride through the bush got us all to base camp by midnight. Surrounded by dense rainforest, the camp was made up of traditional bamboo and reed buildings called Benhabs. These provide shelter from two major expedition dangers – blazing sun and pouring rain. Both can damage the human body in a short space of time. Parrots watched us from the trees, and small monkeys swung high in the branches. A tarantula wandered into camp one evening causing great consternation. Troops from the Guyanese Army gave us some last minute tips in jungle survival before we split up into our groups and deployed to our project sites.

Because of its tropical location traveling in Guyana is an expedition within itself. In the dry season the roads are dust-bowls, choking engines and people alike. In the wet season they are rivers of mud making even the largest four wheel drive vehicles flounder. Ex British Army Bedford lorries are the normal mode of transport, usually traveling in two’s or three’s to help each other in case of breakdown. The rivers are navigable but littered with waterfalls and rapids allowing only localised travel. The adventure group had to travel over 300miles south to its project site; so flying was the only viable option. We met a supply lorry at the halfway point and drove to the Ireng River, as close to Karasabai as possible. We transported half a ton of supplies to the village by Ox and Cart.

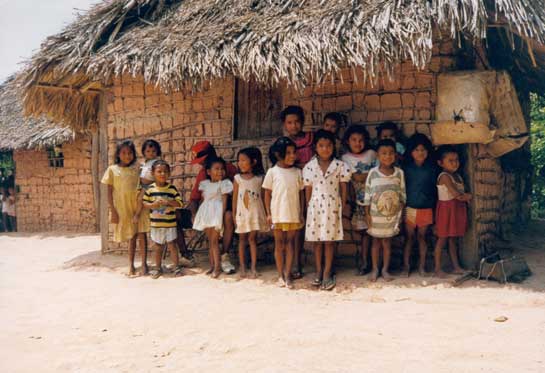

Situated in southern Guyana, Karasabai is a small Amerindian village surviving on subsistence farming. Our project was twofold- to re-build the crumbling village water system and to teach in the small school. Our supplies included yards of water pipe and fittings, and teaching materials such as paper, pencils and textbooks With local help, work on the water supply started straight away. There were over 300yds of pipe to lay, and standpipes to be installed at the School, Police Station and Village Square. We worked early morning and late evening as it was over 100F in the midday sun. The school children were wonderful pupils and teaching them was great fun. After lessons, plastercine models proved to be the favourite pastime.

We left Karasabai early one morning for a six day trek to the village of Kato. Accompanying us were a guide and some Droggers. These are local porters who helped carry our heavy equipment. Their loads are bound into woven bags called warashi’s. One man will carry over 100lb’s wearing flip-flops and drinking only one bottle of water a day. We needed modern rucksacks, walking boots and 6-8 bottles of water a day. We moved on village-by-village, day-by-day, until after four days we arrived at Monkey Mountain. The country had changed from dense rainforest to open savannah, and we toiled in the burning sun. Another two days over savannah brought us to Kato, our journeys end. Since the trek began most of us had lost over a stone in weight.

At 741ft high, Kaiteur is the second highest free fall waterfall in the world. The Potaro River pours over the cliffs giving one of the most spectacular sights in nature. The roar is deafening and spray rises hundreds of feet from the valley below. I sat and marvelled for hours, mesmerized by the turbulent waters. The falls were named after an Amerindian chief who paddled over the waters edge to win favour of the gods in a war against the Carib settlers. Apparently it worked! Sir Walter Raleigh once visited the area in a quest to find the fabled “El Dorado”, the city of gold. In the distance you can see Mt. Roriama, the mountaintop plateau that inspired Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to write “The Lost World”. Every evening clouds of swallows gather in the skies above and dive through the falling waters to roost on the cliffs. It is the most wonderful feat of nature I have ever seen. It was here that all the project groups met up. We had only been apart for just over two weeks, yet had hundreds of experiences to talk about. The Environmental group had worked in the remote Iwokrama nature reserve studying Amazonian Otters. The Construction team had re- built a footbridge at a women’s hostel near the capital, Georgetown, and finally the Medical group had worked in a leprosy hospital at Mahica. It was there where we all moved for our final project.

Television portrays the jungle as an uncomfortable and dangerous place to be. It is hot, humid and smelly. With a little training and preparation however, it can be a wonderful environment full of diverse life and colour. Rivers team with strange fish. The locals catch many varieties including piranha. Multi coloured bird’s squawk high above in the trees, occasionally you find bright feathers on the forest floor. To see nature at her best you need patience, lots of it. Animals can hear your footsteps from a great distance and disappear into the undergrowth, but if you wait then snakes, monkeys and spiders can appear. The mosquito is your greatest enemy, and protecting yourself from them is very important. Malaria is rife in these climates and can be deadly.

Mahica is a sad and run down place. It is an old army camp, which was converted into a leprosy hospital earlier this century. The patients often spend their lives here shut away from society. The Medical project had been constructing a chapel of rest and giving basic medical help where they could. The patients found the influx of new faces stimulating; boredom is a big problem in the hospital. Though not physically demanding, the work tested even the strongest nerves. The hospital also houses a school for abandoned children, and it was here that the final project took place. We had two days to build an adventure playground. The work was extremely hard; we hardly stopped day or night, but handed the playground over to the school ahead of time. There were too many hands for the one project and many spent their time carrying out small repairs all over the hospital.

I pondered over this question long and hard after my return home. I came up with the following answers. There are many lessons we could learn from the South American Amerindians. They live a simple life, suffering few of our western vices, such as materialism and profiteering. The world’s rainforest is shrinking at an alarming rate and must be protected. Logging and prospecting threaten its very existence. It holds most of the world’s nature and combats global warming. Working at Mahica brought home to me the reality of some people’s situations. We so easily shut such people away and they become forgotten.